Introduction #

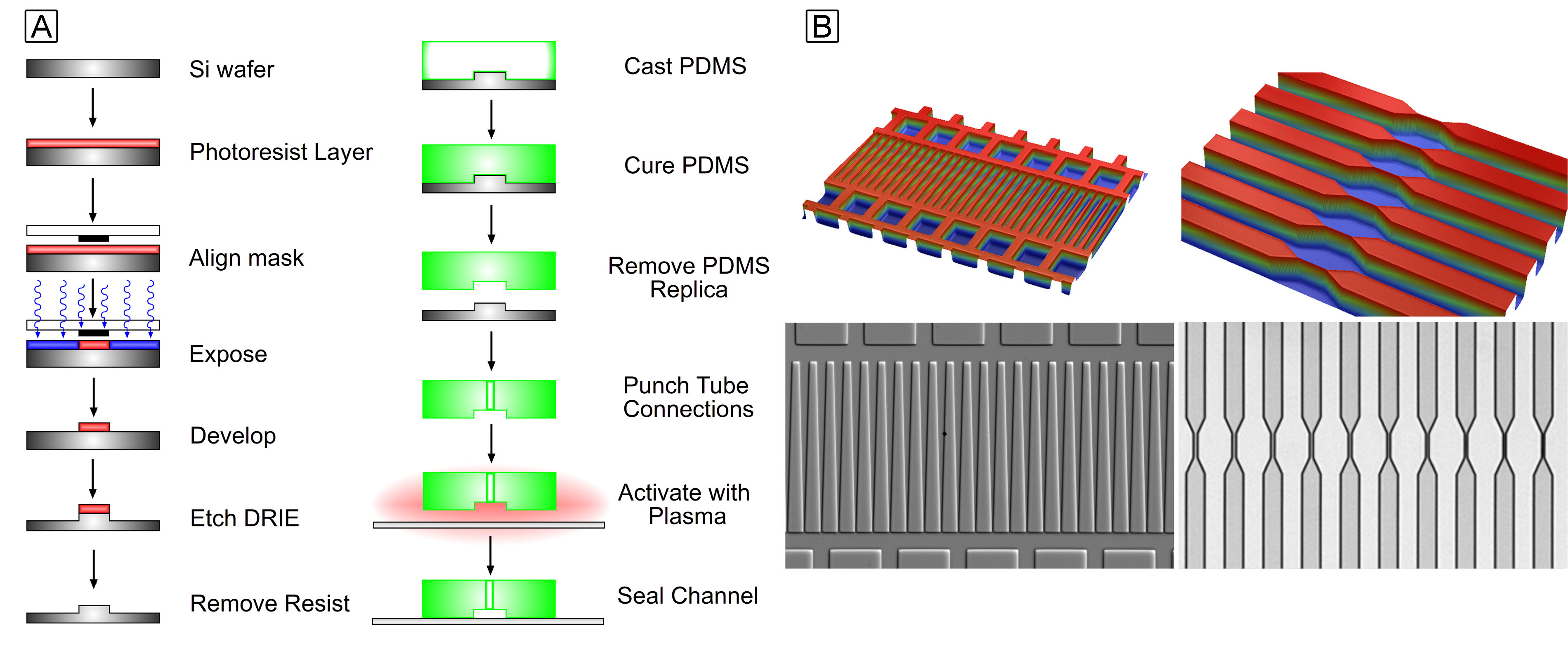

After my work in nanotechnology, I became interested in developing microfluidic devices to study malaria pathogenesis during my graduate studies and postdoctoral research. I designed and fabricated devices to measure the surface area and volume of red blood cells as malaria parasites grew within them. These projects involved creating single-layer PDMS-glass microfluidic devices using silicon master molds.

I chose single-layer devices without on-chip valves because they were faster and more cost-effective to develop, given the limited cleanroom fabrication time and budget. Additionally, these simpler devices were more reliable due to fewer bonding points and were easier to assemble, ensuring a sufficient number of devices to provide the statistical power needed for the study. I also developed methods to produce small production runs of approximately 500 devices for a clinical study conducted in Blantyre, Malawi.

Microfluidics and Malaria Deformability #

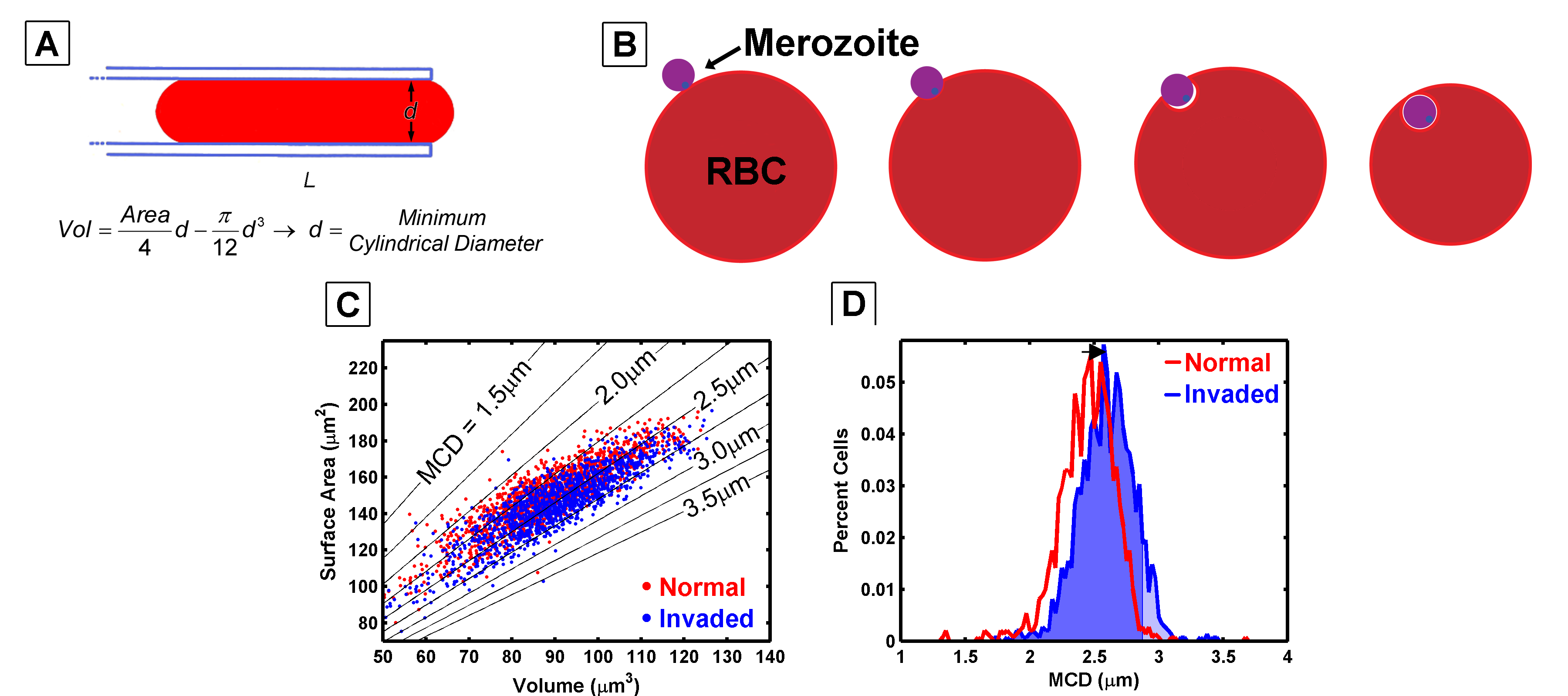

The smallest cylinder or pore a cell can fit through has a linear relationship with its surface area and volume (A). When a malaria merozoite invades a red blood cell, it wraps itself in the cell’s membrane, reducing the surface area and increasing the cell volume (B and C). These changes in surface area and volume shift the minimum cylindrical diameter (D), ultimately making the cells more susceptible to filtration.

Malaria invades and develops within red blood cells (RBCs), extensively modifying the host cell as the parasite matures. The parasite incorporates its own proteins and lipids into the RBC membrane, altering both the cell’s volume and surface area. These changes affect the cell’s deformability, effectively increasing the likelihood that parasitized RBCs are filtered out by the spleen.

The goal of this work was to investigate how red blood cells are filtered by the spleen, where they must deform to navigate a tortuous path. This process can be likened to deforming a cell to fit through a cylinder of a specific diameter. By calculating the surface area and volume of a cell, we can estimate the smallest cylinder diameter through which the cell can pass without expanding its surface area. This technique allows us to determine whether a filter is likely to segregate cells based on their geometry.

Schizont-stage parasitized red blood cells are characterized by the dark hemozoin stain, which settles much higher in the wedges than in normal red blood cells (A). Schizonts have a larger volume and a similar surface area compared to normal red blood cells (B). When the minimum cylindrical diameter is calculated, schizonts are estimated to be unable to pass through a filter with pore sizes smaller than 3 \(\mu\)m (C). In contrast, ring-stage parasitized red blood cells, taken from a malaria patient, penetrate almost as far into the wedges as normal red blood cells (D). However, the surface area and volume of ring-stage parasites (E) overlap with those of normal red blood cells. Their calculated minimum cylindrical diameter suggests that these cells cannot be effectively segregated by passage through a porous filter or a tortuous path (F).

Wedge-shaped channels were used to measure the surface area and volume of cells trapped within the wedge by analyzing the length and depth to which a cell penetrated the channel. The differences between schizonts (mature malaria-infected red blood cells) and ring-stage cells (recently invaded red blood cells) are evident in the following images.

This project successfully developed a model to describe how malaria parasites are filtered by the spleen. However, no significant differences were observed in the geometry of red blood cells or malaria parasites based on their presentation at admission. This finding is important because it rules out red blood cell geometry as a contributing factor to the severity of malaria infection.

Malaria Cytoadhesion to Endothelial Cells #

As malaria parasites remodel their host red blood cell, they create knobs that appear on the surface of the parasitized RBC. These knobs contain proteins that adhere to proteins expressed on the interior surfaces of capillaries in specific organs, such as the brain, lungs, or intestines.

Malaria remodels red blood cells and places protiens on the surface that bind to ligands expressed by endothelial cells in specific organs. When malaria parasites bind to endothelial protein-C receptors (EPCR), the deadly condition known as cerebral malaria can develop. This was research that was performed before the parasite-EPCR interactions were known.

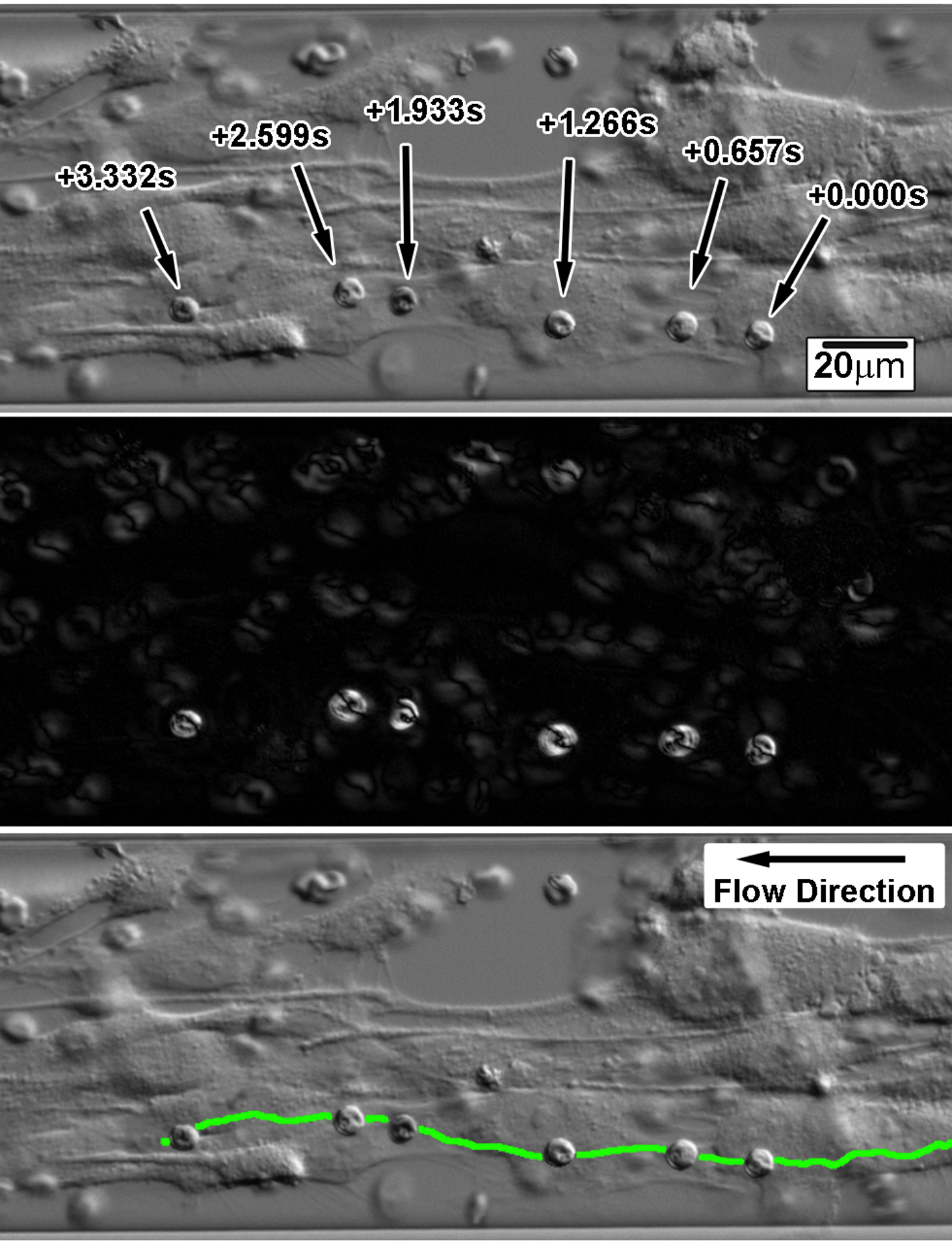

I developed a microfluidic culture system to grow primary endothelial cells in microfluidic capillaries (pictured above). Instead of using on-chip microfluidic valves, I employed stop-cock manifolds due to the additional instrumentation and fabrication costs, which couldn’t fit within an R-21 budget. The culture system was mounted on microscope stage inserts, allowing the devices to be transferred from the incubator to the biological safety cabinet, to the microscope for experiments, and back to the incubator, all without altering any fluidic connections. The only interruption in flow occurred when electrical connections were briefly removed. A pressure sensor measured the pressure drop across the channel, providing feedback to a peristaltic pump to control flow rates. These flow rates were gentle enough to allow the growth of endothelial cells in the microfluidic chambers and capillaries while maintaining constant flow.

Endothelial cells could be seeded and allowed to grow to a lawn over the course of several days.

We were able to observe and quantify parasite-endothelial cell interactions. While this was interesting, we were unable to observe a large number of interactions because the total surface area available for interrogation in the microfluidic capillaries was the limiting factor.

Malaria Cytoadhesion to Purified Ligands #

There were two main issues with measuring parasite-endothelial cell interactions:

- Rolling on endothelial cells appeared to be a rare event.

- We didn’t know whether the parasite var-gene expression matched the receptors on the endothelial cells.

As a result, we couldn’t observe many interactions, and the few we did observe were not well-characterized. I then turned to finding a more controlled system and started a collaboration with Joe Smith’s lab, which had genetically well-characterized parasite strains with stable gene expression. These strains expressed well-known receptors, and the ligands ICAM-1 and CD36 were commercially available and could be easily adsorbed onto glass. I manufactured flow cells using the same techniques I used for making the microfluidic devices, creating flow cells that could record large populations of parasites and measure specific parasite-ligand interactions.

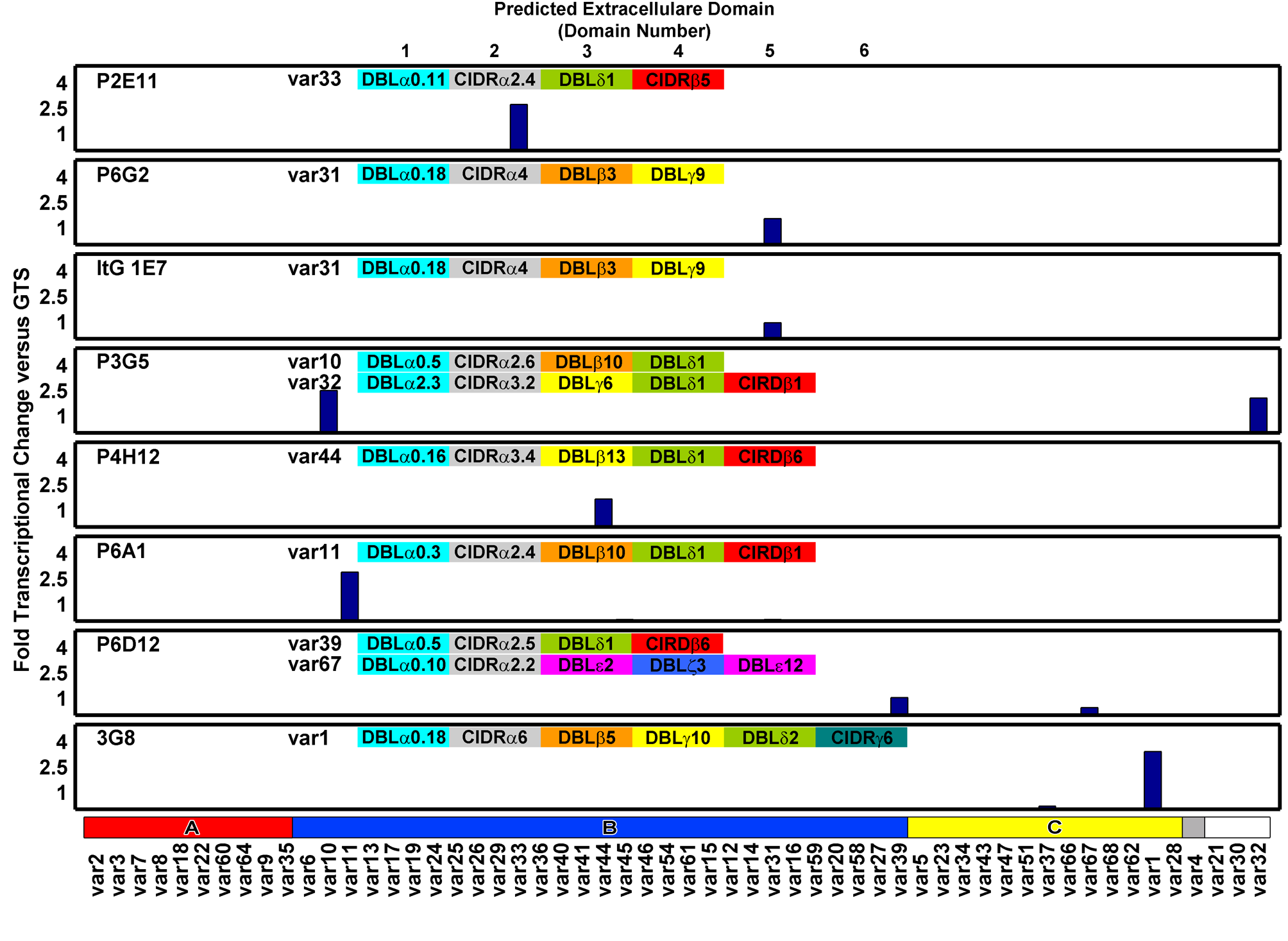

I characterized the gene expression of these ItG parasites using Q-PCR and then measured their rolling velocities on ICAM-1 or CD36 adsorbed onto glass in flow cells.

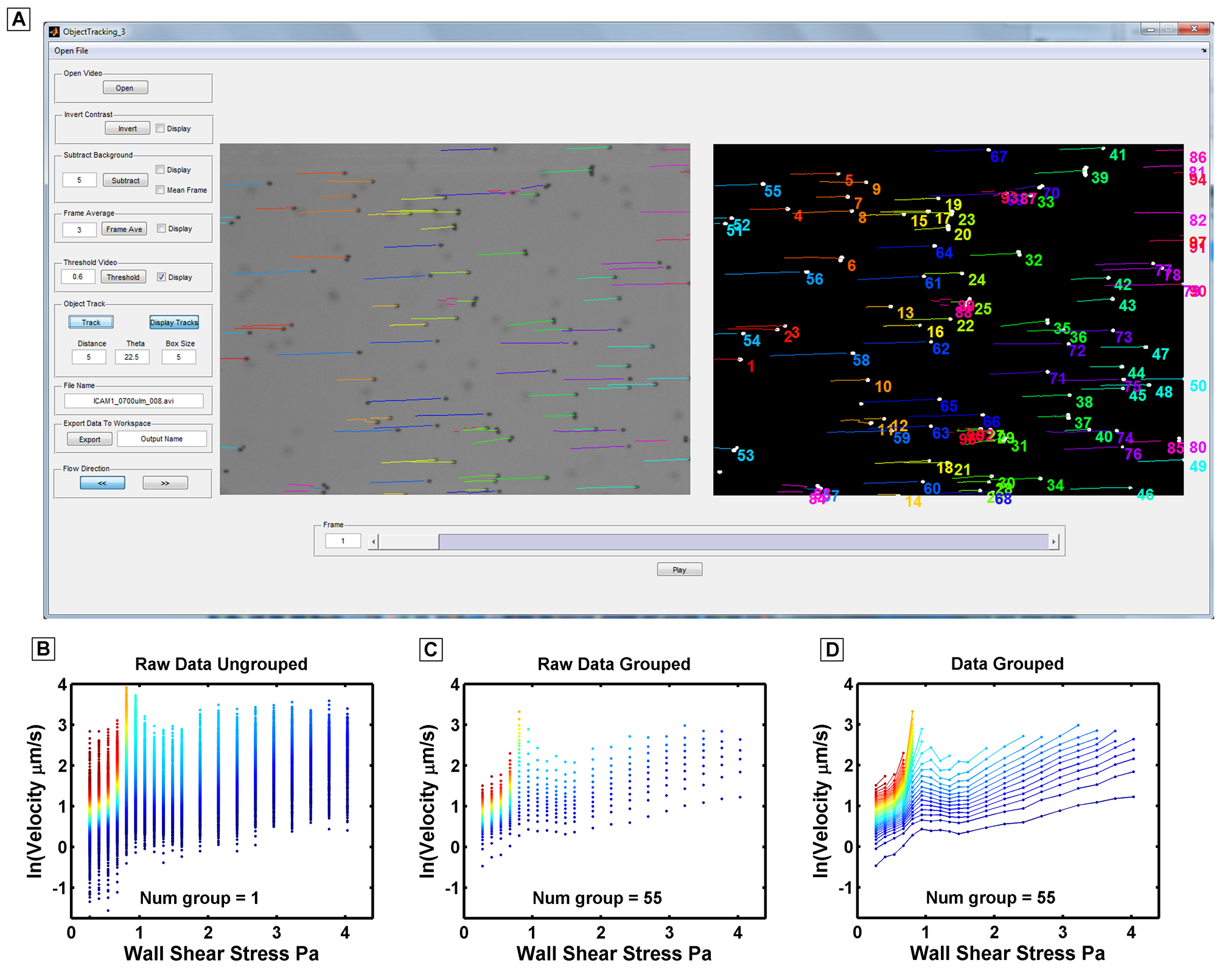

Here is a MATLAB GUI that I wrote and used to extract rolling velocites of malaria parasites imaged in the above videos.

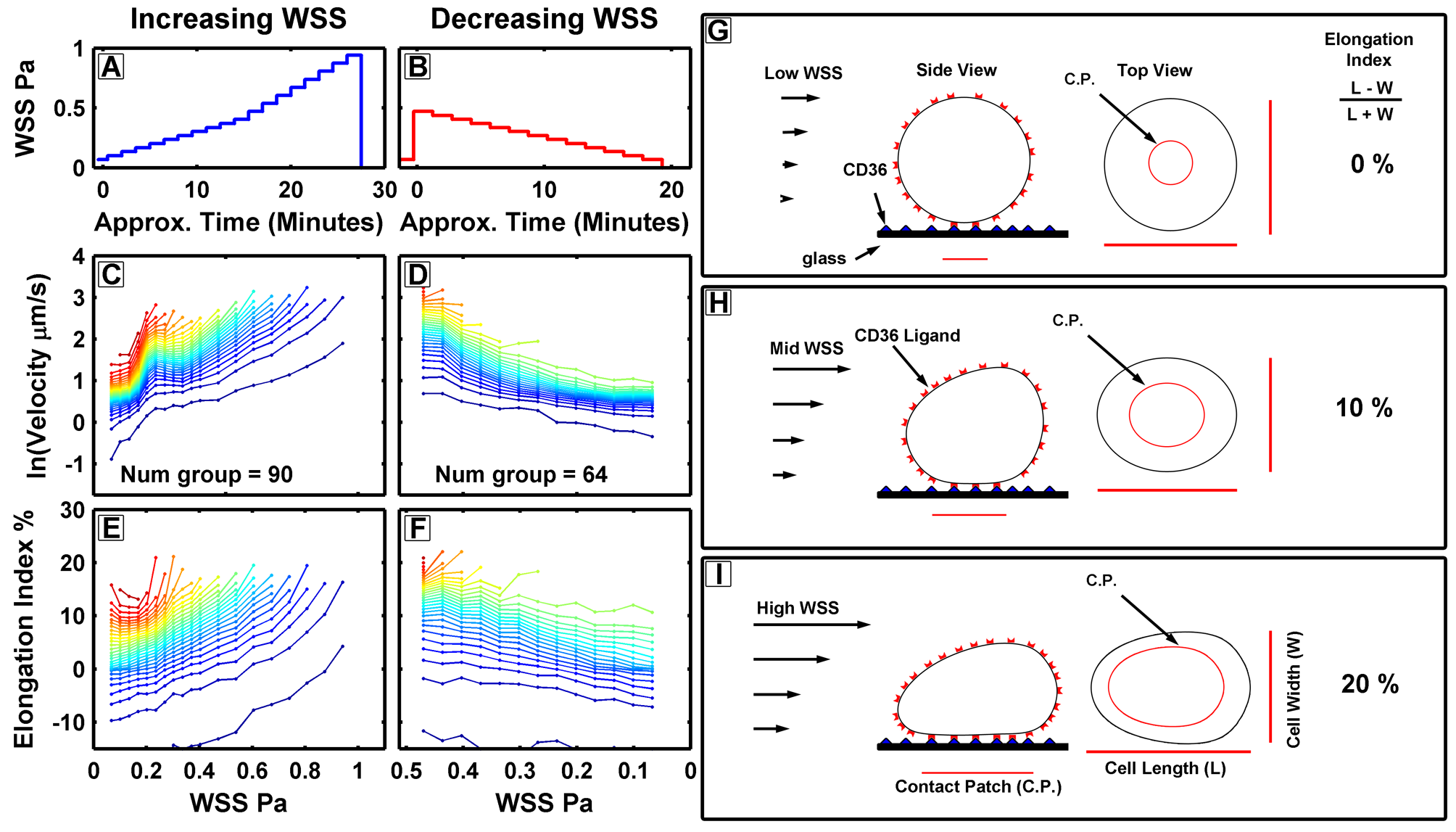

The model depicted above was developed from observations that, as fluid flow increased within a specific range, the parasite’s rolling velocities would either remain the same or, in some cases, actually decrease. This phenomenon is attributed to the wall shear stress created by the flowing media, which presses cells against the glass. This effect increases the surface area of the cell in contact with the glass, thereby increasing the number of ligand-receptor interactions and making the parasites ‘stickier.Consequently, the rolling velocity of the cells decreased as the fluid flow rate increased.

These experiments served as a good demonstration of biomechanics, especially since the shear stress, which caused the cells to flatten against the glass, corresponded to the shear stresses experienced in the post-capillary venules, where parasites are observed to accumulate. This is where deformation directly affects parasite survival because, if they were unable to deform, they would be less sticky and might remain in circulation, potentially getting filtered by the spleen.